Navigating Fantasy Maps by M. D. Presley (WORLDBUILDING BY THE NUMBERS)

One goal of Worldbuilding for Fantasy Fans and Authors was compiling and synthesizing all the varying worldbuilding theories and best practices gleaned from fantasy authors and the worldbuilding communities. And along the way, I realized that, outside of the gaming and RPG community, very few worldbuilders take the audience’s experience into account, which was why I included several surveys in my book. Unlike authors, who have to sometimes wait years for feedback of their worlds in the form of reviews, gamers get instant feedback from the players, which helps shape the world in turn. So with that audience-focused approach in mind, I’m kicking off a (hopefully) monthly fantasy worldbuilding series here on the Hive, with each one examining survey results about each topic to see what fans really think of aspects of fantasy world.

One goal of Worldbuilding for Fantasy Fans and Authors was compiling and synthesizing all the varying worldbuilding theories and best practices gleaned from fantasy authors and the worldbuilding communities. And along the way, I realized that, outside of the gaming and RPG community, very few worldbuilders take the audience’s experience into account, which was why I included several surveys in my book. Unlike authors, who have to sometimes wait years for feedback of their worlds in the form of reviews, gamers get instant feedback from the players, which helps shape the world in turn. So with that audience-focused approach in mind, I’m kicking off a (hopefully) monthly fantasy worldbuilding series here on the Hive, with each one examining survey results about each topic to see what fans really think of aspects of fantasy world.

And first up are maps in fantasy books.

Maps of places that don’t exist have existed centuries before the modern fantasy novel, but many consumers automatically expect maps as a part of Tolkien’s legacy by including one in Lord of the Rings. The iconic opening to the Game of Thrones focused on the map itself, and considering that Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones were both massive gateway series for many fantasy fans, this should illustrate the importance of fantasy maps within the genre. In researching for my worldbuilding book, I found that 77% of audiences appreciate a map, nearly tying with in-world myths as their favorite ancillary inclusions.

Conducted nearly a year later, this survey backs up this preference for maps, with 87% of participants stating they enjoyed maps, and the next 12% being indifferent to maps. Only 1% of participants stated they did not enjoy the inclusion of maps.

So it sounds like all fantasy stories better include maps, right?

Well, no.

Conversely, the same 88% of participants stated maps were unnecessary for fantasy stories. This means fans enjoy their inclusion, but do not begrudge the authors when they aren’t there. And this apparent paradox should probably feel par for the course in a genre whose goal is making the unreal feel real.

I’ve joked before that maps are really just visual info dumps at the onset of the story where the author is literally imparting the lay of the land before the story even begins. Instead of letting the audience experience the setting, they are given an overt overview; a literal bird’s-eye view. In this sense, the map acts as a bit of a prologue, which is something that has fallen out of vogue in novels (although, as I pointed out before, prologues work great for info dump equity). Some readers claim to skip them entirely so they can start the story when the story kicks into gear in chapter one.

The survey backs this notion up, with 30% stating they spend most of their time with the map before the story begins, 35% in the first quarter, and another 23% in the second quarter. This means about 88% of audiences spend most of their time with the map BEFORE the first half of the book is over. It should be noted that they will consult the map multiple times as well, with almost a third saying they pore over them nine times or more, and only around 10% saying they only look at maps once or not at all.

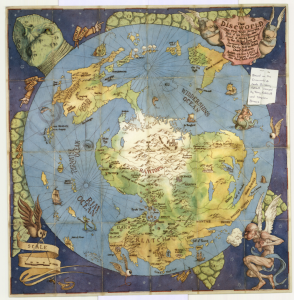

Although Steven Erikson once told the anecdote about how he and his writing partner Ian C. Esslemont objected to how unrealistic a Dungeons and Dragons map was, most audiences do not care if the maps adhere to real-world geography, with only 18% saying it’s important, and 10% saying “very important.” This means nearly three-quarters do not care, or consider geography inconsequential, although it should be noted that this was a very general question worthy of further exploration. It’s one thing to say you don’t care on an intellectual level, and quite another to see a tundra right next to a tropical rainforest. But most people don’t care so long as the map has face validity.

The Discworld, drawn by Stephen Player to the directions of Terry Pratchett and Stephen Briggs. Editor’s Note: Pratchett consulted experts in order to ensure his geography made sense.

One concept Mark J. P. Wolf explores in his book Building Imaginary Worlds is the Illusion of Completeness, which is part of one of the 4 Cs of Worldbuilding and basically boils down to making the reading experience more immersive by giving the audience hints there’s more to the world than they are encountering in the story. The fantasy world should feel like it began before the present story and will continue after the current storyline is over. This is frequently accomplished by offhandedly alluding to histories and locations that do not directly affect the story so that audiences get a sense there’s always more to explore. The survey backs this up, with 79% of participants stating that maps should include locations not encountered in the story.

Ironically, these additional, ephemeral locations help the world feel more real.

Personally, I believe a lot of the “fast travel” complaints about the last season of Game of Thrones sprung from the prominence of the map in the opening credits. Audiences are primed each time the show begins to think of the vast scope of the continents, which was why they objected so strongly when characters suddenly moved so quickly when the plot demanded it. Many authors list this as a reason not to include a map, and even Tolkien himself retconned some travel times in the second edition of The Hobbit to make them fit with his Lord of the Rings map. The understanding is that once the map is penned, the author is beholden to it. However, audiences do not agree with this assessment, with 78% stating that when the map contradicts the text of the story, the text is correct. So this, along with the fact audiences don’t mind if authors deviate from the laws of nature, should give authors a little breathing room in fashioning their maps.

Senlin Ascends by Josiah Bancroft

As to the scale of the maps, audiences want to go big, with 25% preferring a world map, 35% preferring maps of the continent, and 19% preferring regional maps. City maps and single settings (a castle/ dungeon) accounted for less than 10% of favorites.

With that in mind, subgenres directly influence what scale of maps audiences expect. Unsurprisingly, because of their focus on quests, audiences expect high/ epic fantasy stories to have world maps, followed closely by continent or regional maps. The same holds true for portal fantasy, military fantasy, as well as sword and sorcery. This makes sense in the case of portal fantasy—where the protagonists are literally encountering a new world—that the audience expects to see; military, where armies are often on the move; and the more wandering sword and sorcery, which frequently encounters new adventures in new locations.

Compare this to urban fantasy, where audiences expect a city map or perhaps a regional map, then not much else. Being that “urban” means “city,” this should be no surprise. Nor should it that crime/ heist stories take place mostly in cities, with single locations and regional maps coming in close second. Because of the technological worldbuilding components of steampunk/ gaslamp fantasy, the city again becomes the most likely scale for the map.

Paranormal fantasy cleaved between the two extremes, with a focus on the regional or city map. More interesting, though, is that this subgenre had the most votes for not needing a map at all, at almost double its closest competitor.

So, while people may prefer large maps, they certainly don’t expect one when the story is on a smaller scale. They also don’t mind if there’s no map at all, as fans of Harry Potter can attest. Authors are also not bound by reality when creating their maps.

This is fantasy, after all.

Please take part in the survey for next time: Elves, Dwarves, and Dragons (oh, my!).

[…] to wonder what these offhand references to history or additional geography entail. This explains, as we discussed last time, why 79% of fantasy fans want maps to include locations not visited in the story […]

Yay for maps! This is a great place to start and I love the surveys. I’ve read some amazing fantasy novels that had no maps at all, but I’ve always felt bad that my own didn’t have any I felt worth a reader’s time. (Squiggles and stick figures aren’t exactly conducive to a magical atmosphere, you know?) Thank you for letting me know that readers might enjoy them, but they aren’t necessary for them to enjoy the story.

Looking forward to the next installment in this series!