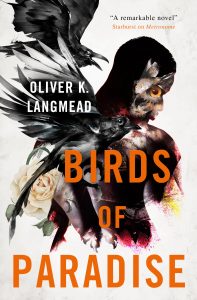

BIRDS OF PARADISE by Oliver K. Langmead (BOOK REVIEW)

“The books are a perfect example, Adam thinks, of reading to confirm one’s own beliefs: they are all theological in nature, and of a very particular slant. They speak to the superiority of man, and his God-given right to possess and exploit the world for his betterment. They give the reader permission to plunder all that is not man, interpreting ancient words for profit. Adam pulls books from shelves, spilling sheaves of notes, flicking through them and discarding them into the waters. Let the floods wash away those words, he thinks. Let those books become pulp. Let them remember that they were once trees, alive and thriving and heavy with leaves.”

Oliver K. Langmead’s previous books, the noir space opera epic poem Dark Star (2015) and music-inspired fantasy Metronome (2017) established him as an ambitious and unique voice in speculative fiction. His new novel Birds Of Paradise (2021) is a similar mix of audacity and invention, a heist novel in which Adam, the first man, and the surviving first animals, must work together to steal the pieces of Eden which have been scattered across the globe. As with Dark Star, Langmead once again takes two genres that on the surface seem about as disparate as they can be – this time round an action-filled heist novel and a theological musing on grief, sin and humanity. In the hands of a lesser writer this would simply be an ambitious mess. Langmead’s great skill is his ability to take such different genres and modes and tease out hidden thematic similarities, to the extent that by the end of the story one wonders how it could have been told in any other way. Birds Of Paradise is at once a fantastical romp that plays with the Christian mythology in Genesis to create a clever postmodern tapestry of story and myth, and a furious attack on the blinkered anthropocentrism which has led to our thoughtless and cruel destruction of the Earth and its creatures in the name of our progress. It is simultaneously loads of fun and profoundly troubling, and all tied together with Langmead’s enviable poetic handling of language.

Adam, the first man, like all the denizens of Eden, is cursed with immortality. He has slipped in and out of various lives down the years, becoming increasingly disillusioned with his children and numb to the world around him. He learns through Magpie, one of Eden’s animals living a secret life as a human, that pieces of Eden are turning up on the Earth. Teaming up with Magpie, Owl, Crow, Crab, Pig and Butterfly, Adam and his friends must track down the missing pieces of paradise from those who would hoard it for themselves, particularly the ruthless billionaire collector Frank Sinclair and his loathsome cult of cronies. Along the way Adam might just come to terms with the all-consuming grief clouding his every thought.

Adam, the first man, like all the denizens of Eden, is cursed with immortality. He has slipped in and out of various lives down the years, becoming increasingly disillusioned with his children and numb to the world around him. He learns through Magpie, one of Eden’s animals living a secret life as a human, that pieces of Eden are turning up on the Earth. Teaming up with Magpie, Owl, Crow, Crab, Pig and Butterfly, Adam and his friends must track down the missing pieces of paradise from those who would hoard it for themselves, particularly the ruthless billionaire collector Frank Sinclair and his loathsome cult of cronies. Along the way Adam might just come to terms with the all-consuming grief clouding his every thought.

From the description of the plot, one might be forgiven for thinking that Birds Of Paradise is a fantastical romp. Much of the book is indeed delightful, alternating between incredibly inventive and unusual heist scenes – the stealing of Eden’s cherry tree from a museum exhibit in broad daylight is a highlight – and Langmead’s skilful weaving of Adam’s story throughout human history. Langmead’s deft interweaving of elements of myth with mundane reality, with Adam and the animals visiting cinemas or wandering the UK’s most recognisable metropolises, is reminiscent of Neil Gaiman’s iconic American Gods (2001). Langmead is particularly good at getting the balance of these characters just right – they are all recognisable and relatable, and we respond to the human elements in them, but Langmead never lets us forget how different these immortals are from us. All the animals very much have an animal nature, and the sheer length of his life and suffering make Adam almost god-like. The way the novel engages with the Christian origin story is interesting – various elements from Genesis resurface throughout the text in unusual or unexpected ways, and Adam himself is frequently in conflict with other interpretations of himself, the weight of all those other readings.

However for all its inventiveness and playfulness, Birds Of Paradise is frequently a very upsetting book. The key theme of the book is the interpretation of the dominion God gives Adam over the animals. Frank Sinclair reads this as meaning that humanity is inherently superior to nature, that nature has been put here as a resource for mankind to exploit as they see fit. Adam, however, sees his relationship with nature as more a caring and nurturing one. He has been a gardener in many of his previous lives. But Adam’s version of the gardener is not the elevated human shaping nature to their will, it is of someone who lives as a part of nature, whose relationship with the natural world is built on the understanding that humanity too is part of the natural world. Throughout the book, Adam is appalled by the unthinking cruelty and brutality with which his children frequently treat animals. Frank Sinclair in particular is emblematic of a humanity that hunts animals for fun, that would hoard natural resources for the private use of him and his friends, that gains a perverse pleasure from physically exercising their dominance over the natural world. But how much of this is specifically humanity’s curse? Adam himself has no particular skill set to bring to Magpie’s heists other than his brute strength. Throughout the book he solves almost all his problems through visceral violence. Birds Of Paradise looks at a humanity which is destroying the world around us with rapacious violence and asks, is this all we are? Have we inherited all of Adam’s anger and violence, and none of his caring and compassion? The book gives no easy answers.

Langmead’s novel is powerful and troubling because it asks these difficult questions. That it manages to be an enjoyable fantasy adventure story at the same time is quite the magician’s trick. I look forward to seeing what else Langmead has up his sleeves.

[…] Birds of Paradise has been described as American Gods meets The Chronicles of Narnia, and has received praise from brilliant writers like Joanne Harris, Ellen Kushner, Francesco Dimitri and R.J. Barker. The Guardian has called it “fantastic and colourful”, SFX has called it “charming, strange and thought-provoking”, and Publisher’s Weekly has called it “meditative and elegant.” [Our Jonathan had some great things to say about it too – review] […]