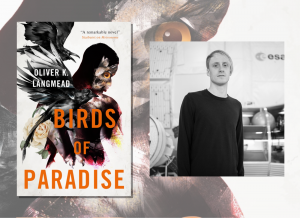

Interview with Oliver K. Langmead (BIRDS OF PARADISE)

Oliver K. Langmead is an author and poet based in Glasgow. His long-form poem, Dark Star, featured in the Guardian’s Best Books of 2015. Oliver is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Glasgow, where he is researching terraforming and ecological philosophy, and in late 2018 he undertook a writing residency at the European Space Agency’s Astronaut Centre in Cologne, writing about astronauts and people who work with astronauts. He tweets @oliverklangmead.

Welcome to the Hive, Oliver. Let’s start with the basics: dazzle us with an elevator pitch! Why should readers check out your work?

What if the first man was still alive today? What if, after he was expelled from the garden, the rest of immortal Eden was deconstructed and scattered across the world? What if some of those pieces of paradise ended up in the hands of a group of wealthy pastoral fetishists? How far would Adam be willing to go to regather the remaining fragments of his lost home, and who among Eden’s undying exiles might help him along the way?

Birds of Paradise has been described as American Gods meets The Chronicles of Narnia, and has received praise from brilliant writers like Joanne Harris, Ellen Kushner, Francesco Dimitri and R.J. Barker. The Guardian has called it “fantastic and colourful”, SFX has called it “charming, strange and thought-provoking”, and Publisher’s Weekly has called it “meditative and elegant.” [Our Jonathan had some great things to say about it too – review]

In what ways are you planning on celebrating the release of Birds of Paradise?

I’ve been privileged to have a launch event co-organised by the University of Glasgow’s Creative Conversations team and Centre for Fantasy (you can see the video here), which was a fantastic opportunity to dress fancy and appear in front of the most outrageous zoom background I could find.

But let me tell you – I dearly miss in-person book launches. Obviously, it’s lovely that online book events are much more accessible and convenient for a lot of people, but there’s nothing quite like reading for an audience in the same room, and chatting with folk, and being able to personalise books for people. Here’s to hoping there’s scope for something in-person at some point over the coming months!

We always appreciate a beautiful book cover! How involved in the process were you? Was there a particular aesthetic you hoped the artist would portray?

Authors don’t get much input on their book covers, which is why I consider myself so lucky that Birds of Paradise looks as excellent as it does. Julia Lloyd is to blame for that. And while I did get to give a little feedback along the way, it’s probably for the best that I stay out of the process. Designing a book cover is an act of interpretation and translation – it’s not my take on the work, but someone else’s. Thankfully, Julia, with the guidance of my wonderful editor, George Sandison, is a canny interpreter.

I also regularly work with an illustrator – Darren Kerrigan – who has contributed a gorgeous new piece to Birds of Paradise, which you can see below.

Your book draws heavily on the Bible, following Adam on a journey to find all the lost pieces of Eden. What about the Christian creation myth attracted you to these characters?

I find Christian mythology interesting in the same way that I find Harry Potter interesting. The Harry Potter universe is rich, and immersive, and has inspired so many wonderful people, but it absolutely does not stand up to scrutiny. It’s a logistical, logical nightmare. So too is Christian mythology. So much of it is moving, and compelling, but it takes a Herculean effort to determine which bits of it should be taken literally, and which bits of it should be taken metaphorically. I basically just took one of Christianity’s prettiest myths and added a layer of logic to it – what if Eden was real? What if Adam was made before death? What if he was still alive today?

The novel is a series of heists to recover the missing pieces of Eden. How did you go about crafting the heists, and how much of a challenge was it?

Writing a good heist, as it turns out, is pretty difficult.

There are three heists in Birds of Paradise, and a reader favourite is the cherry tree heist, which happens to be the one I found the most challenging to write. The set-up is simple enough (if ambitious) – how might the first man and his friend steal a cherry tree from a central London art gallery? In the end, it took me six months to find the solution. I made so many different elaborate plans, none of which felt at all satisfying. Then, it came to me all at once, one sunny day, sitting in Glasgow’s Botanical Gardens. Sometimes coming up with the ideal solution to a writing problem is simply giving it space and time to develop in your head.

I am very proud of the cherry tree heist, and I hope it’s one you enjoy.

You feature many characters who are animals from Eden, but who also have a human aspect. Which one was the most fun to write?

Writing Eden’s immortal animals was an absolute pleasure, and I love them all for different reasons. Rook’s sharp mind, Owl’s ferocity, and Butterfly’s colourful creativity were a joy to bring to life. I suppose that Magpie has been in my head for the longest, though. Back at the very start of the book, when I needed a collector to be gathering together the lost pieces of Eden, he emerged so vividly. I love his eccentricity – his playful cynicism about humanity. And I love his silver sequinned jacket.

Tell us a little something about your writing process – do you have a certain method? Do you find music helps? Give us a glimpse into your world!

Ritual and habit rule over longer pieces of writing. It’s about making a space for the work to inhabit – physically and mentally. But I like to change my habits and rituals, depending on what I’m writing. For Birds, I would always go for a long walk through green spaces before sitting down to write. Then, I’d find a nice, quiet place, and let myself become absorbed in it. I wrote most of it up in a lovely balcony on campus at the University of Glasgow, overlooking trees and following the colours of their leaves as the seasons rolled by.

Birds of Paradise and Metronome are written in prose, whilst Dark Star, your first book, is a noir epic poem. How do writing prose and poetry differ? Do you always know which medium an idea will be told through when you first get it?

Definitely not! Dark Star was originally going to be in prose, until a series of experiments proved fruitful enough for it to emerge in verse instead. Similarly, the new long-form poem I’m writing was conceived as a work of prose, but has ended up in verse because it just seems to suit the story I’m telling. For me, form is an extension of storytelling. Dark Star works in verse because its sparse stanzas represent the voice of the (literally and figuratively) dark city they inhabit, obscuring the reader from seeing beyond the glimmers of light in the gloom. For Metronome, which is an expansive odyssey, working in flowing prose feels like making it a cup overflowing with colour.

I love being able to write both poetry and prose. To me, writing poetry feels like solving a puzzle (finding satisfaction in crafting each line), and prose feels like writing on an endless canvas.

Every writer encounters stumbling blocks, be it a difficult chapter, challenging subject matter or just starting a new project. How do you motivate yourself on days when you don’t want to write?

Sitting down to write every day is important to me because writing habitually is far more effective than writing to inspiration. That being said – some days, when I sit down, I absolutely cannot make words form on the page. Of course, this is absolutely fine. The very act of trying makes sure that I maintain the habit. And I always know, even if I find myself unable to produce good work for a few days (or weeks!) in a row, that I will produce something I like again if I just keep persisting.

It’s important to not put too much stress on yourself to produce volume. Sometimes, a good writing day is a single line, or a single paragraph, and you should be able to derive just as much satisfaction from that as you might from having written an entire solid scene.

From science fiction to fantasy to noir to epic poetry you seem to enjoy playing with genres and creating new, unexpected combinations. What draws you to this?

I feel a bit like China Mieville, who is known to be working through every different genre he can find. Dark Star was science fiction noir, Metronome was a portal quest, Birds of Paradise is mythical fantasy, and I’m currently finishing off a dystopia and a science fiction epic. Just as much as form is an extension of storytelling, I think that genre is as well, and I am privileged to be able to continue switching from genre to genre as I’d like.

I think I like doing this for the same reason that I don’t really write sequels. When I sit down to write a book, I want it to end so that I can go somewhere else. There’s nothing I like more in fiction than being taken somewhere new. And being able to play with genre lets me go to some very strange and unusual places!

What (or who) are your most significant fantasy/sci-fi influences? Are there any creators whom you dream of working with someday?

What (or who) are your most significant fantasy/sci-fi influences? Are there any creators whom you dream of working with someday?

I have a shelf filled with my favourite authors beside me, to remind me what good writing is on those days when it feels like I can’t write at all. On that shelf are the likes of Pratchett and Gaiman and Pullman, along with Ali Smith, China Mieville, Susanna Clarke, Michel Faber, Brian Catling, Shirley Jackson, Jeff Vandermeer and Raymond Chandler. I don’t imagine there being any surprises there – but I do come from a background of fantasy. In that way, I suppose that writing science fiction feels like a bit of an indulgence sometimes – it’s not a genre I’m quite as well read in as I’d like, yet.

It’s strange to imagine myself working with anyone. Writing is such a solitary pursuit, and from experience I find it a bit tricky to let go of creative control. That being said – every writer dreams of having their work filmed, and there are a few directors I would love for my work to go to. Most prominently, Alex Garland, who has yet to release a film or TV series I haven’t absolutely loved. My work tends to be described as vivid and aesthetic, and working with a director who could evoke those things would be a dream.

Can you tell us a bit more about your characters? Do you have a favourite type of character you enjoy writing?

My protagonists tend to be fairly broken, flawed people. Virgil, in Dark Star, is an addict, Manderlay, in Metronome, is an arthritic musician, and Adam, in Birds of Paradise, has complex trauma. I love seeing them survive, and thrive, and find hope against the odds, and I love finding little moments of beauty for them to enjoy. Exploring their flaws opens my writing up to a lot of richness, as well – unravelling why Virgil is so hostile towards the poverty-stricken inhabitants of his city, and why Adam is so apathetic towards his descendants, is an exercise in thinking through and confronting all-too-real human biases.

The world shifts, and you find yourself with an extra day on your hands during which you’re not allowed to write. How do you choose to spend the day?

Every now and then, maybe twice a year at most, myself and a few friends book out a hostel up in the Scottish glens for a weekend, and go out there to play games, cut off from phone signals and the internet. It’s so dark out there that you can see the stars properly, and the wind is sharp enough to cut. There are small streams, and high hills, and pines, and you can walk for hours without seeing anyone. We light bonfires, and eat too many snacks, and this past year in lockdown, I’ve missed those trips the most.

Sounds like balm for the soul!

One of our favourite questions here on the Fantasy Hive: which fantastical creature would you ride into battle and why?

This really depends on the kind of battle, where it’s taking place, and my role in it. Am I fighting an army, or other fantastical creatures? Is it happening in the sky, or the sea, or a forest? Am I in command, or a part of a vanguard? Luckily, fantasy lets us create chimeras, so let’s go with that as my answer. Not the classic mythical chimera – but a chimera of my own making, fine-tuned for the battle at hand.

Of course – it will look fabulous, and match my outfit.

Tell us about a book that’s excellent, but underappreciated or obscure.

One of my favourite books is Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger. It was his last book, and the most well-known version of it is a work of fraud, perpetrated by Twain’s executor. In fact, Twain never finished writing it, and the version that was published in 1916 was three different unfinished manuscripts stitched together. Despite this – the fraudulent version is a powerful work of fantastical satire, and absolutely succeeds (which is perhaps why it took until the 1960s for scholars to notice what had happened). If you’re a fan of Mark Twain, I strongly suggest reading The Mysterious Stranger – it is, I think, one of his greatest works, and remains unappreciated because of the circumstances surrounding its release. A fabulous piece of fraudulent fiction.

What’s next for Oliver Langmead?

I’m just in the process of editing my next book with Titan, called Glitterati. It’s a fabulous, colourful dystopian satire, and I can’t wait to see the cover (and share it!). Look out for that at some point in 2022. Otherwise, I’m just finishing my doctorate, which is, in part, a new long-form poem. I’ve spent a good few years working on that poem – called Calypso – and I’m looking forward to seeing if my lovely agent can find a home for it. A work of careful joy.

Finally, what is the one thing you hope readers take away from your writing?

There is always hope. No matter how broken and tired you might feel, there is always some small glimmer of brightness to find.

Thank you so much for joining us Oliver!