The Four Cs of Fantasy Worldbuilding (WORLDBUILDING BY THE NUMBERS)

One goal of Worldbuilding for Fantasy Fans and Authors was compiling and synthesizing all the varying worldbuilding theories and best practices gleaned from fantasy authors and the worldbuilding communities. And along the way, I realized that, outside of the gaming and RPG community, very few worldbuilders take the audience’s experience into account, which was why I included several surveys in my book. Unlike authors, who have to sometimes wait years for feedback of their worlds in the form of reviews, gamers get instant feedback from the players, which helps shape the world in turn. So with that audience-focused approach in mind, welcome to Worldbuilding by the Numbers: a monthly fantasy worldbuilding series here on the Hive, with each one examining survey results about each topic to see what fans really think of aspects of fantasy world.

One goal of Worldbuilding for Fantasy Fans and Authors was compiling and synthesizing all the varying worldbuilding theories and best practices gleaned from fantasy authors and the worldbuilding communities. And along the way, I realized that, outside of the gaming and RPG community, very few worldbuilders take the audience’s experience into account, which was why I included several surveys in my book. Unlike authors, who have to sometimes wait years for feedback of their worlds in the form of reviews, gamers get instant feedback from the players, which helps shape the world in turn. So with that audience-focused approach in mind, welcome to Worldbuilding by the Numbers: a monthly fantasy worldbuilding series here on the Hive, with each one examining survey results about each topic to see what fans really think of aspects of fantasy world.

This month, The Four Cs of Fantasy Worldbuilding.

In many ways, the study of worldbuilding mirrors story structure in that neither is absolutely necessary. People have been making up stories and worlds long before we ever considered studying them, and it’s completely possible to create a world-changing story without studying the craft at all. Like story structure, worldbuilding “rules” like the four C’s aren’t any more stringent than the break to the second act or increasing urgency at the midpoint. They are simply patterns observed in hundreds of successful fantasy and science fiction stories that authors can choose to use or ignore as they see fit. Mark J. P. Wolf was the first to uncover these patterns in his worldbuilding textbook Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation. However, he only listed three (Invention, Completeness, and Consistency), which make for the icky acronym I.C.C.

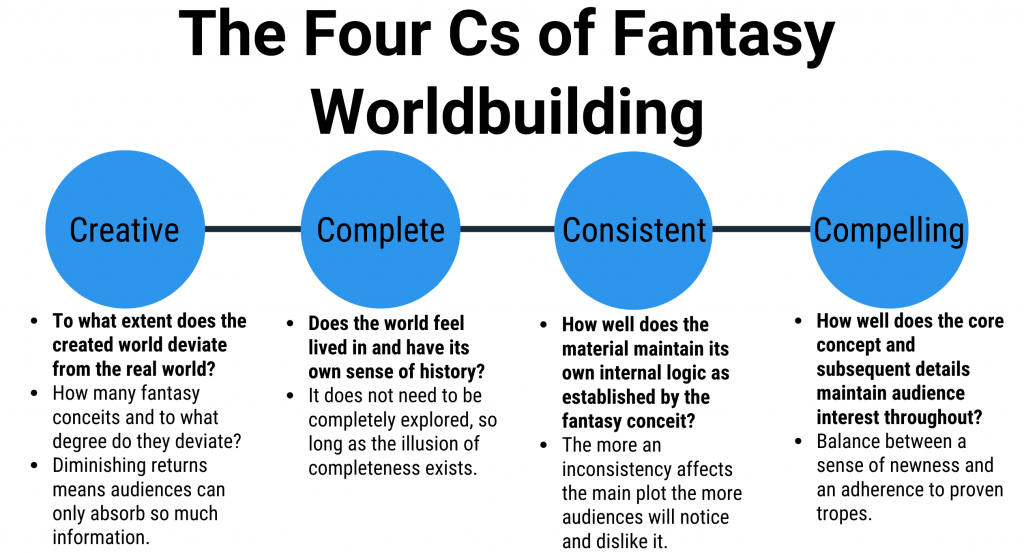

One of the ironies of fantasy worldbuilding is that effective worldbuilding usually goes unnoticed because the audience is absorbing all the details in an unconscious, immersive state. It’s only when this state is disturbed, usually by breaking one of the four Cs of worldbuilding, that the audience is ejected from the story in the same way than a typo can disrupt the reading flow (yes, that one was intentional). Taken alone, these breaks in immersion are not usually deal-breakers, but they add up quickly to eventually ruin the experience, which is why the four Cs are meant to keep the audience’s experience as seamless as possible. So, without further ado, let’s introduce you to the four C’s: Creative, Complete, Consistent, and Compelling.

Creative deals with how often and to what extent the constructed world deviates from the real world.

Jemisin calls this “element X,” and it is also known as fantasy conceits, or what the creator wishes to examine in the world. The creative component is also what makes the genre fantasy in the first place since it’s made up of the unreality the audience craves. This is why we read the genre, after all.

Each fantasy conceit can create massive changes to the world in question, and it’s worth noting that Harry Potter only has three major conceits: 1) magic exists, 2) otherworldly creatures like goblins, giants, and dragons exist, 3) ghosts exist. Yet a whole world was wrought from those changes to the extent that there are now theme parks dedicated to its worldbuilding. Even Middle Earth, the granddaddy of all modern worldbuilding, in only has about five fantasy conceits total, yet still holds our attention 70 years later.

Tolkien was the first to point out that anything in the world not covered by one of the fantasy conceits must adhere to the audience’s understanding of the real world. So rivers should not flow uphill UNLESS that’s a integral point of the worldbuilding that the author intends on exploring. Tolkien also believed that all fantasy conceits should be explored to their fullest, and named changes made to the world that have no effect “nominal changes.” Nominal changes, to Tolkien, were just window dressing used to make the world feel exotic without putting in the real work of making it logically sound.

Although creative changes are why we read the fantasy genre, they have their downsides. Like any spice, a small amount enhances the meal, but too much can be overpowering. In terms of creative concepts, the laws of diminishing returns means that each new deviation from the real world loses some of its punch. And too many deviations can eventually become alienating for the audience.

Complete means it should feel that the world exists before the story begins, has regions that are unexplored within the current story, and will continue to exist after the story is over (provided the heroes save the world, of course).

Like characterization in a story, these are the details that make the world feel well-rounded instead of a flat cardboard cutout. One of the reasons that Star Wars caused such a splash when it debuted in 1977 was because the world(s) felt real and lived in, with machines that broke down and required repairing, food processors for making meals, and even games for the characters to play. Also, with a single line of dialogue from Obi-Wan, the sense of history was cemented with a mention of “the clone wars” that later went on to inspire a movie as well as two TV series.

That offhand referral to the clone wars is one of the best examples of what Wolf calls the “illusion of completeness,” which is giving hints of the wider world within the story opposed to spelling out every single detail. This air of mystery goes a long way by engaging the audience’s imagination and allowing them to wonder what these offhand references to history or additional geography entail. This explains, as we discussed last time, why 79% of fantasy fans want maps to include locations not visited in the story itself.

Consistent means that the world does not contradict itself or deviate from the laws of nature as we understand them.

Consistent means that the world does not contradict itself or deviate from the laws of nature as we understand them.

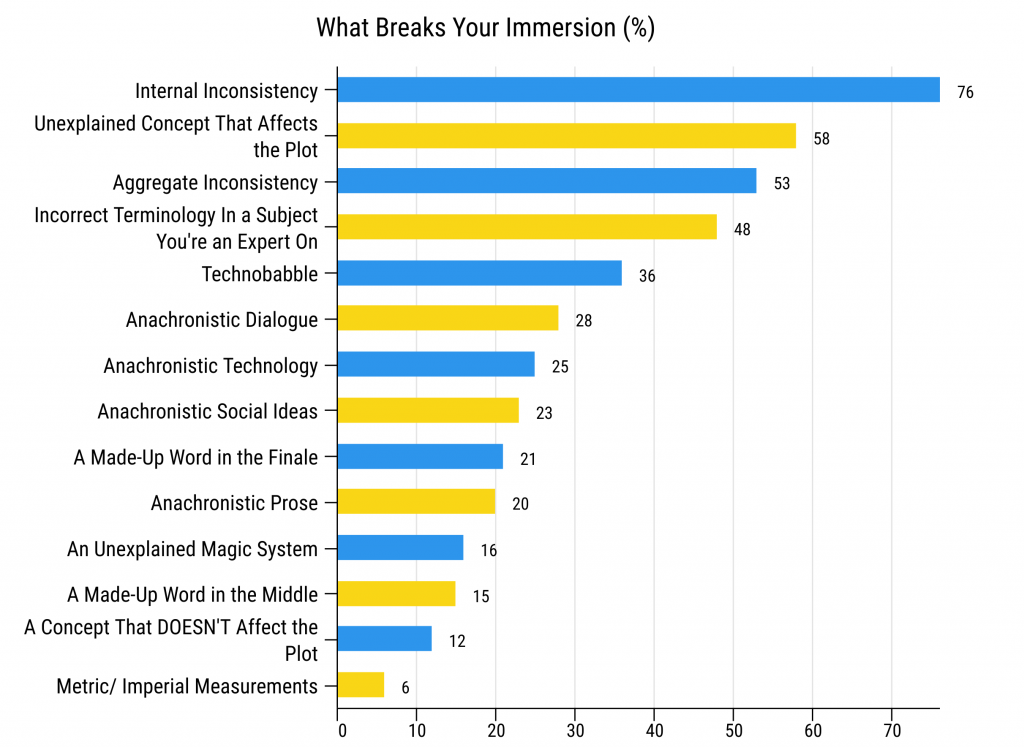

When surveyed, fantasy fans rated internal inconsistencies as the number one way to break immersion. This was a clear 20 points higher than second place, and goes to show how much audiences pay attention to the author’s fantasy conceits and expect the author to adhere to the rules they created. Aggregate inconsistencies came in third, and are made up of inconsistencies across a series rather than those within the same single story, making inconsistencies two of the only three type of breaks in immersion to crack 50%.

However, as we mentioned in the section on Creative, anything not directly under the umbrella of a fantasy conceit is meant to adhere to the rules of the real world. Jemisin echoes Tolkien here when she points out that audiences consider themselves experts of this world, which is why they use their understanding of it to gage the veracity of the created world. This expectation for real-world consistency for anything not covered under a fantasy conceit is known as terra de facto, which deserves its own blog post in the future.

It should also be noted that inconsistencies are not a deal-breaker for a world, as illustrated by the 200+ aggregate inconsistencies catalogued in the Harry Potter series. Tolkien and Lucas have also done extensive retconning to clean up inconsistencies in their works, which are still well-beloved, which demonstrates that any break in the three first Cs of worldbuilding can be forgiven so long as the material is compelling.

Compelling means that the material resonates with the consumer and maintains interest.

In many ways, Compelling is the most nebulous of the four Cs since it’s the most personal and hardest to measure. Each person is different, and what is inspiring for one person can be boring for another. But a good rule of thumb for measuring this C is how long the audience will maintain their willing suspension of disbelief.

Other than critics, most consumers go into a new story with the desire to be entertained; to escape from their daily life by entering a new world (literally, in the case of fantasy). Because of their initial interest, the consumer starts off in a permeable state where they willingly absorb all the new details of the world. They reserve judgement for a short while so they can get a lay of the land and a feel of the story. But this goodwill does not last forever, and the author must entertain the audience to keep them engaged. Anecdotally speaking from my years working in screenwriting assessment, the willing suspension of disbelief lasts for about the first act, at which point the audience becomes critical of the material. This does not mean that they are actively trying to tear the story or world apart, rather that they now think they understand the underpinnings of the world, characters, and plot and feel comfortably judging if the author lived up to their expectations based on what they absorbed during the period of goodwill. In effect, the audience is now actively employing the other three Cs…

…so long as they’re not absolutely enthralled by the material that is. If they’re constantly getting dopamine pops from great story twists, character reveals, and a sense of wonder from a fascinating world, they will ignore any strains to the other three Cs. And because the goal of genre authors is to entertain their audiences, they frequently rely upon what’s worked in the past, which is how tropes like elves, dragons, and dwarves (our next subject), or kidnapped princesses and farm boys with magic swords continue to exist nearly 100 years into the genre’s modern era. Audiences flock to fantasy with certain expectations in mind, which the author must adhere to if they wish to succeed. And in a way it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (another trope) because the author includes tropes because they are popular, but they are popular because authors keep using them, so they are now what audiences expect.

Authors’ adherence to tropes demonstrates how the four Cs can also work against each other. Audiences want new worlds to explore, thus engaging the Creative aspect, but all these new deviations from reality can clash with their genre expectations in the Compelling component. Adding more and more details to make the world feel Complete makes it harder to keep all those details Consistent, especially when a series goes on for many years or has multiple authors, as is the case with Star Wars. All these components and moving parts illustrates why making a successful fantasy world is so difficult, and why authors must keep each component in balance, not only against the other Cs, but between the top-down concepts and the bottom-up details employed to get these concepts across.

So keep these four Cs of worldbuilding in mind, both authors who want to create fascinating new worlds, and for fantasy fans to better appreciate the fantasy worlds they so dearly love.

[…] recently encountered this post by M D Presley on ‘The Four Cs of Fantasy Worldbuilding,’ and it sparked my imagination. Specifically, the idea of a fantasy conceit: a way in which a […]

Fantastic post; I struggle with keeping my world’s internal consistency as I write. I love it when workers “break ” their rules, but it is still consistent with the world when you look back. The Mistborn series is great for this. I try too hard as a new writer to pull this off, and I have not mastered it just yet.