WOMB CITY by Tlotlo Tsamaase (BOOK REVIEW)

“In our city, it is unwise to trust reality.

I have been betrayed by reality, betrayed by my subconscious, shipwrecked from reality.

Now every thought must be deceased from my mind before its birth.”

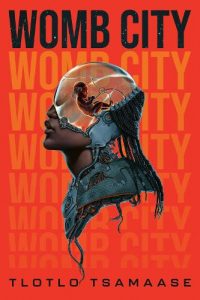

Tlotlo Tsamaase is a Motswana writer who has established herself as one of the most exciting current voices in short speculative fiction. Her novella The Silence of the Wilting Skin (2020) is a surreal body horror nightmare quite unlike anything else I’d ever read before. So I was very much looking forward to Tsamaase’s debut novel Womb City (2024), especially when I saw that Erewhon Books had graced it with one of the greatest SF covers I’d seen in a long time, courtesy of artist Colin Verdi and designer Samira Iravani. Womb City delivers and then some. A work of cyberpunk body horror set in a near future dystopian Botswana, the novel redefines what those genres can do, offering a powerful feminist exploration of female embodiment, pregnancy and abuse. The book draws on Setswana mythology as much as cybernetic science, and seamlessly mixes cyberpunk speculation and horror. Tsamaase has created a vital and urgent work of speculative fiction that makes the reader excited for what the genre can do all over again.

Nelah is the head of an award-winning but financially struggling independent architecture firm in a near-future Botswana where body-swapping is possible thanks to technology, but because she is a woman and her body is marked as having criminal tendencies, she is monitored constantly by microchip. Both the government, with its AI Criminal Behavior Evaluator, and her abusive husband Elifasi, a policeman who blames his lack of career progression on his wife, can track her every move and sift through her memories. Nelah’s life is precarious – she self-medicates with casual drug use, has an affair with the handsome Janith Koshal, a forensic structural engineer she met through work, whose father Aarav Koshal is a ruthless, corrupt and powerful businessman, her body’s family resent her for taking the place of their beloved daughter. But now with a baby growing in a government incubator that she and Elifasi can barely afford, she is under extra scrutiny because she is about to become a mother. When Nelah and Jan kill a woman in a car accident, they bury the body, hoping against hope that they’ll both be able to keep it a secret. But soon she has more to worry about than the government and her husband – the vengeful spirit of her victim returns from the grave to hunt down everyone Nelah holds dear. In order to escape from the curse and make sure her baby survives, Nelah has to solve the mystery of the dark political conspiracy their victim was investigating at the time of her death, before the ghost and the government catch up with her.

Nelah is the head of an award-winning but financially struggling independent architecture firm in a near-future Botswana where body-swapping is possible thanks to technology, but because she is a woman and her body is marked as having criminal tendencies, she is monitored constantly by microchip. Both the government, with its AI Criminal Behavior Evaluator, and her abusive husband Elifasi, a policeman who blames his lack of career progression on his wife, can track her every move and sift through her memories. Nelah’s life is precarious – she self-medicates with casual drug use, has an affair with the handsome Janith Koshal, a forensic structural engineer she met through work, whose father Aarav Koshal is a ruthless, corrupt and powerful businessman, her body’s family resent her for taking the place of their beloved daughter. But now with a baby growing in a government incubator that she and Elifasi can barely afford, she is under extra scrutiny because she is about to become a mother. When Nelah and Jan kill a woman in a car accident, they bury the body, hoping against hope that they’ll both be able to keep it a secret. But soon she has more to worry about than the government and her husband – the vengeful spirit of her victim returns from the grave to hunt down everyone Nelah holds dear. In order to escape from the curse and make sure her baby survives, Nelah has to solve the mystery of the dark political conspiracy their victim was investigating at the time of her death, before the ghost and the government catch up with her.

Womb City takes the cyberpunk trope of people being able to upload their consciousness digitally and implant it in new bodies, as popularized in works such as Richard Morgan’s Altered Carbon (2002), and uses it to explore the complex ways in which embodiment, privilege and discrimination are tied together. In the Botswana of the novel, citizens are entitled to multiple lifespans across multiple bodies, but this is complicated by the lack of supply of desirable bodies. No one wants to be stuck in the timeless living hell that is being stored in between bodies in a databank, but the past history of the body you are uploaded into has a massive bearing on your new life inside it. Bodies like Nelah’s host body, which are marked as criminal, are subject to intrusive surveillance, with the cyberpunk technology allowing the government and partners alike to directly scroll through their thoughts and memories. The immigration system to other countries involves body-swapping into bodies that are already citizens of the country you are trying to get into, but the convoluted and corrupt bureaucracy around it means that you run the risk of your body being sold to the black market before you secure a new body. The concept of the nuclear family is beginning to break down, with people being assigned the biological families of their new bodies, regardless of whether or not the new family accepts them. Of course all this can be circumvented if, like Aarav Koshal, you are rich and powerful, and indeed he has wielded his considerable influence to get his son Janith a fresh body to hide family crimes. However those like Nelah who don’t have the money or connections to get a more privileged body are stuck with the limitations society places on the body they wind up in.

This is further complicated by the brutal criminal justice system explored in the novel. Citizens are obliged to take a CBE test annually, where, like in an unholy mash up of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report (1956) and ‘We Can Remember It For You Wholesale’ (1966), they are subjected to a virtual reality simulation that determines whether or not they are likely to commit a crime in the future, in which case they will be removed from their bodies and stored in the databanks while someone on the waiting list will inherit their body along with its family, social connections and wealth. Things are even more restricted for women, who are microchipped and subjected to intense surveillance that tracks their every move, all under the excuse of “protecting” women from sexual assault. Tsamaase brilliantly extrapolates the end point of a society that blames the female victims of sexual assault for the crime they have been subjected to, imagining a future where all women are essentially pre-labeled as criminals, the prosecution of the victim taken to its horrendous dystopian extreme. The novel is very much concerned with the societal expectations placed on women, from the way that corporate culture enables and covers up sexual assault by bosses on employees, to the higher standards that women are held up to when they are mothers, to the ways that the state can act hand-in-hand with male abusers to keep women in abusive relationships and protect the abusive men from any consequences.

All this is fascinatingly wrapped up in Setswana culture. Tsamaase explores how the physical reincarnation offered by the body swapping technology interacts with and disrupts the traditional belief in reincarnation – characters frequently grapple with the question of whether or not this digital afterlife is preventing them from entering into their ancestors’ spiritual afterlife. And the novel’s plot of government conspiracy, surveillance and manipulation of citizens is linked to the mysterious Murder Trials, a form of punitive justice linked to a much older conception of human sacrifice that is connected to Matsieng, a mysterious and ancient deity that emerged from a system of underground caves. The end result is a novel that could only be written by a Motswana writer, one that effortlessly fuses hard cybernetic SF, speculative fiction about societal development, and ghost stories fuelled by traditional beliefs. Tsamaase masterfully ties together all these seemingly disparate strands into a cohesive whole that imparts huge amounts of information and worldbuilding without ever having to resort to info dumping. It’s also a furious, politically engaged novel that unflinchingly faces the misogyny of the modern era and demands that the system be torn down and reborn as something better, something uncompromisingly Other. Womb City is an incredible work of speculative fiction, an early contender for the book of the year. And I can’t wait to see what Tsamaase will do next.

Womb City is available now, you can order you copy on Bookshop.org