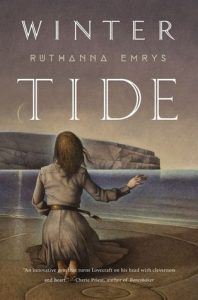

Winter Tide by Ruthanna Emrys

“It’s one thing to say that humanity is ultimately unimportant in the face of the cosmos. It’s another to stand before someone who believes, deep down, that your pain is trivial.”

“It’s one thing to say that humanity is ultimately unimportant in the face of the cosmos. It’s another to stand before someone who believes, deep down, that your pain is trivial.”

“We’re all monsters, or related to monsters, one way or another.”

H. P. Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1936) is one of the writer’s most iconic stories. Exploring a decaying New England fishing town with a dark secret, it displays Lovecraft’s atmospheric sense of place, the gothic extremes of his imagination as he evokes some of the more powerful images from his mythos, and even sees him writing an effective and memorable action sequence. However, the story is also fuelled by Lovecraft’s vile racism; its narrative is built on Lovecraft’s ludicrous fear of miscegenation, and its protagonist suffers an inevitable decline as a result of his own “contaminated” ancestry. Reading the story today, one can’t help but feel a real surge of horror where Lovecraft most likely didn’t intend it – the denizens of Innsmouth, after the protagonist reports to the government that they are hybrids resulting from the interbreeding of humans and Deep Ones, monsters from the sea, are captured and sent off to internment camps.

Ruthanna Emrys’s novel Winter Tide (2017) brilliantly subverts the original Lovecraft story by giving us the story of Aphra Marsh, one of the only two Innsmouth survivors from the camps. In 1949, as she tries to rebuild her life in the outside world, she is contacted by FBI agent Ron Spector, who needs her help in recovering secret documents Communist agents have stolen from Miskatonic University, before they are used to put the existence of humanity itself in peril. This set up allows Emrys to tell an exciting Cold War spy tale using mythos elements whilst interrogating the problematic aspects in Lovecraft’s original stories.

Emrys draws elements from The Shadow Over Innsmouth to examine ideas about race and systematic persecution, but she also draws on Lovecraft’s loose follow up, the misogynistic and transphobic body-swapping story The Thing On The Doorstep (1937) to explore ideas of sexuality and gender that would have made Lovecraft uncomfortable. She also takes elements from The Shadow Out Of Time (1936), in particular the Yith, body-swapping aliens who amass history and culture from forgotten races in their great library city, to play with Lovecraft’s favourite theme of the cosmic insignificance of humanity, and what this means in the light of humanity’s inhumanity.

Winter Tide manages to balance itself sensitively between the pulp aesthetic of Lovecraft and the horrors of the real world. Aphra’s adopted family is the Kotos, Japanese Americans who were sent to the internment camps when the US joined World War II. By linking Aphra and her brother Caleb’s fate to the real life experience of Japanese Americans during the war, Emrys is able to show us the horrors of both the Holocaust and the American internment camps through fresh eyes.

The sections that show flashbacks of Aphra and Caleb’s time in the camps are sparse and brutal, with no supernatural or fantastical elements. They effectively convey the horrendous inhumanity that humanity is capable of, as well as the moments of genuine affection and kindness between the Marshes and the Kotos in spite of the horror that surrounds them. By linking the fictional to real world suffering, the book also forces the reader to reflect on the horrendous racism displayed in Lovecraft’s original story. Although it is a work of cosmic horror and not realistic fiction about actual peoples, the fact that Lovecraft can end the story with casual mass incarceration and genocide of an entire people is indicative of an attitude that must be confronted.

Bringing Lovecraftian fiction forward to the Cold War is a fertile plot idea that allows Emrys to give her story its own particular flavour. The story is told in the first person by Aphra, whose voice is calm but full of hidden pain and sorrow, contrasting nicely with the grandiloquent hysteria of Lovecraft’s damaged scholars. Winter Tide brings out the similarities between Lovecraft’s Weird Fiction and the spy thrillers of the Cold War era. Both are predicated on the idea that the world we see around us is a fragile illusion that can be shattered by secret knowledge, which must be kept from the general public for this exact reason.

Both are also built on paranoia; Emrys smartly ties the paranoia of Lovecraft’s body-swapping stories with that of McCarthyism. The idea that Communists could use Yith techniques to masquerade as high-ranking US military officials is all the excuse the FBI needs to crack down on human rights. It’s a deft piece of political satire, and one that is all too relevant in our current climate of political paranoia and the resurgence of the authoritarian right.

One of the reasons Aphra and Caleb agree to help Spector is so that they can gain access to the books in Miskatonic University that were stolen from Innsmouth in the government raid. Much of the book is a powerful look at what it’s like to have your culture stolen from you and erased. Aphra and Caleb are denied access to the Miskatonic collection, which contains not only Innsmouth’s occult texts but also diaries and personal records that survive their friends and family. They face institutional racism from the university staff and patronising attitudes from the students in their quest, people who still see them as either degenerate monsters or an exotic curiosity.

In one of the most moving sequences in the book, Aphra goes to the University chapel to pray, where she finds that, in spite of Miskatonic’s suppression of her people’s beliefs, the architect of the cathedral found subtle ways to honour his faith. There she prays to her people’s gods, the Elder Gods of the mythos, whilst considering how each one failed her and her people in their time of need. It’s a raw and powerful piece of writing that stays with the reader.

Aphra and Caleb are outsiders, persecuted by their government and seen as alien and frightening by others. Winter Tide explores institutionalised prejudice and persecution not just through them but also through its diverse cast of supporting characters. Neko Koto, Aphra and Caleb’s adopted sister, also faces prejudice because of her Japanese heritage, and shares their trauma from growing up in the internment camps. Spector works for the government but as a gay Jew is constantly having to prove his loyalty to the FBI and America and lives in fear of his sexuality being found out. Charlie Day, Aphra’s friend, colleague and acolyte, is also gay, something he has to hide from his friends and society. Audrey Winslow is a student of Hall School, as a woman she is not allowed into Miskatonic in spite of her intelligence and aptitude for the occult, and her desire to study is not taken seriously by anyone apart from Aphra, who takes her on as another acolyte. She is also descended from the Mad Ones Under the Earth, and so like Aprha and Caleb is related to monsters. Professor Trumbull is a female professor at Miskatonic who has been replaced by one of the Yith. Miss Dawson, posing as a secretary at Miskatonic but actually an FBI secret agent and expert in Russian, is an African American woman, forced to live a secret life as the Dean’s mistress in order to act as the FBI’s eyes in Miskatonic. The complex relationships of the ethnically and sexually diverse cast celebrate the wide array of human experience and humanity, while their complicated pasts and the persecutions they suffer remind us how easy it is for people to demonise sections of humanity, to no longer see them as human.

It is in its exploration of the humanity of Lovecraft’s monsters, and the monstrous inhumanity practiced by humans, that Winter Tide achieves much of its drive and power. The Yith inhabiting Professor Trumbull serves as a constant reminder of the transience and insignificance of all human existence; humans, Deep Ones and Mad Ones Under the Earth alike are as temporary as mayflies in the eyes of such an ancient and dispassionate being. However Emrys’s novel is about different people coming together and finding their shared core of humanity despite their differences. Aphra and Caleb’s team of misfits work together to save the human race.

The book ends with a subversion of the grisly blood rituals overseen by Deep Ones armed with sacred knives that is a source of much horror in a lot of Lovecraftian fiction – here the ritual is carried out not to harm, but to save the lives of friends. Thus Emrys turns Lovecraft’s main theme on its head – in the face of vast, cosmic indifference, perhaps all that matters is how we treat each other.

This review appeared on Fantasy-Faction on July 10, 2017.