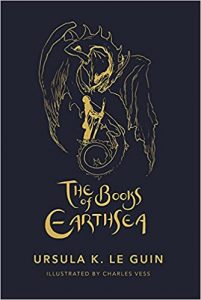

THE BOOKS OF EARTHSEA by Ursula K. Le Guin (BOOK REVIEW)

With a new illustrated edition of all Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea writings just published, there has never been a better time to immerse oneself in works of fiction that justify her acclaim as the Grand Master of fantasy.

With a new illustrated edition of all Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea writings just published, there has never been a better time to immerse oneself in works of fiction that justify her acclaim as the Grand Master of fantasy.

It all begin with A Wizard of Earthsea, a story about a young man known as Sparrowhawk who will become a ‘dragonlord and Archmage’. Born and raised on the island of Gont in the Earthsea archipelago, he becomes known for what we would now call occult powers but such an ability is not unknown in Earthsea and he is packed off to a wizard school on the island of Roke. Here he learns some serious magic, fraught with frightening possibilities and demons of his own making. What follows is an odyssey that becomes a search for his own identity.

Apart from being a thrilling Bildungsroman, there are two especially noteworthy aspects to the first novel set in the archipelago. First, Sparrowhawk is dark-skinned and it is the plundering Kargs, attacking Gort in the first chapter, who are ‘white-skinned, yellow-haired’. The book was first published in the US in 1968 and, even if his colour did register with publicists (‘I didn’t make an issue of it,’ says le Guin), any illustration depicting a non-white hero was unthinkable. For years, he duly appeared as a young white boy on front covers of the book.

The other point to note, three decades before JK Rowling gave a similar education to her sorcerer, is Sparrowhawk’s attendance at a school for wizards. Le Guin was diplomatic enough not to accuse Rowling of plagiarism while making an important critical observation: ‘I didn’t feel she ripped me off, as some people did, though she could have been more gracious about her predecessors. My incredulity was at the critics who found the first book wonderfully original. She has many virtues, but originality isn’t one of them. That hurt.’ More pointedly, she has summed up the limitations of Rowling’s Harry Potter books: ‘a lively kid’s fantasy crossed with a ‘school novel’, good fare for its age group, but stylistically ordinary, imaginatively derivative, and ethically rather mean-spirited.’

The Tombs of Atuan, the sequel to A Wizard of Earthsea, introduces a young girl, Tenar, who was born in the Kargish empire and taken to be a high priestess to the ‘Nameless Ones’ at the Tombs of Atuan. As the result of her encounter with Ged (Sparrowhawk’s real name), she also has to examine her own life although the full consequences of this process – confronting a male-dominated world – do not become apparent until a separate book, Tehanu, appears in 1990. Long before then, however, the story of how the young sorcerer from Gont completes his existential quest reaches its philosophical conclusion in The Farthest Shore (1973).

Image-by-loulou-Nash-from-Pixabay

It was Ged’s pride that, in A Wizard of Earthsea, led him to summon a spirit from the dead, a deed that opened a tear in the world’s fabric and allowed in a shadowy beast of unbeing. As the story unfolds in the books that follow, it becomes possible to see this beast as a part of Ged’s own self and in The Farthest Shore there is a final confrontation that re-enacts this encounter with his own nature. He learns that there will always be dragons blocking your way and that, ultimately, there is no magic that gets you through life’s changes. Taoist and Buddhist reflections are there in the writings’ background but without, as Le Guin puts it, the ‘God business’.

The novels’ appeal to adults and younger readers has not declined over the years – the trilogy has never been out of print – and it was only a matter of time before Le Guin was encouraged to write more stories set in Earthsea. Over the years, these have amounted to over half a dozen additional texts and they are all included in the definitive new publication, The Books of Earthsea.

The extra material begins with Tales from Earthsea, a set of five tales that explore or extend the world first created in the four earlier novels, and includes a lecture, ‘Children, Women, Men and Dragons’, Le Guin delivered at a university conference. In it, she considers how in the Western tradition ‘ heroism has been gendered: the hero is a man’ and why she wrote Tehanu as an act of affirmative action.

The nearly one thousand pages of The Books of Earthsea amount to a landmark publication and make amazingly good value as a necessary purchase, the literary equivalent of a box set of all the Beatles recordings. There are nearly sixty illustrations including many in colour, by an artist, Charles Vess, who worked with Le Guin on all of them. It’s a shame she never lived to see the book in print but she knew what it would look like and gave it her blessing.