BLOOD RED by Gabriela Ponce translated by Sarah Booker (BOOK REVIEW)

“I wallow on the bathroom tiles, a red dot in this white universe. My solitude is writhing in a pain I never understood. I think about the red bird flapping its wings, making a path for itself in the brightness of the white, of the ice, of the snow, landing on our tree, us naked, watching it. The two of us in bed, the two of us in the kitchen, the two of us on the balcony. We were enclosed points, the red birds visiting us. To miss is a feeling of impotence that traps and rips me open, there’s nothing else, just a mistimed entity that drowns between my thighs.”

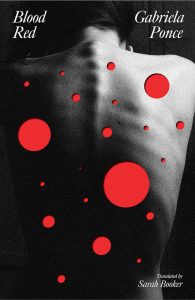

Gabriela Ponce is a writer from Ecuador, where her novels, short stories and plays have received awards and critical acclaim. Blood Red (2020, translated by Sarah Booker 2022) is her first book to be published in English, and reveals her to be a powerful and transgressive voice in literary fiction. Published last year in the US by Restless Books, Blood Red is now brought to the UK thanks to Dead Ink Press, who have done us an incredible service bringing this unique voice to a UK audience. Ponce’s novel defies easy categorization. A stream of conscious narrative from the perspective of a woman leaving a messy divorce, Blood Red is a striking story of female agency, of the messiness, joy and terror of embodiment. But I would argue it contains strong elements of horror and the speculative, as Ponce unflinchingly dissects her protagonist’s most lurid fears and obsessions, fixating on blood and orifices. The end result is an intense and unsettling reading experience that is unlikely to leave the reader unchanged.

Blood Red’s unnamed narrator is a thirty-eight-year-old woman whose marriage is on the verge of collapse. The novel follows her inmost thoughts, as she responds by embracing her new life of freedom and abandon. She has lots of casual sex, takes a whole bunch of drugs, skates round the city at night and goes to parties with her friends. And she chronicles both her luxuriations in her bodily pleasures and her pain, signified by her body’s bleedings and her intense trypophobia. She has an intense affair with her man in a cave – a beautiful unnamed man who lives in a dingy flat under some stairs, surrounded by musical instruments and his numerous cats, whilst feeling jealous of his relationship with his daughter. She gets drunk with her friend María as she packs up her estranged husband’s belongings. She has a nervous breakdown and is sent to a retreat. But all this is upended when she becomes unexpectedly pregnant with the man in the cave’s child, causing her to flee to her childhood pen pal, a poet who shelters her while she decides what to do, as her body undergoes ever more intense transformations.

Blood Red’s unnamed narrator is a thirty-eight-year-old woman whose marriage is on the verge of collapse. The novel follows her inmost thoughts, as she responds by embracing her new life of freedom and abandon. She has lots of casual sex, takes a whole bunch of drugs, skates round the city at night and goes to parties with her friends. And she chronicles both her luxuriations in her bodily pleasures and her pain, signified by her body’s bleedings and her intense trypophobia. She has an intense affair with her man in a cave – a beautiful unnamed man who lives in a dingy flat under some stairs, surrounded by musical instruments and his numerous cats, whilst feeling jealous of his relationship with his daughter. She gets drunk with her friend María as she packs up her estranged husband’s belongings. She has a nervous breakdown and is sent to a retreat. But all this is upended when she becomes unexpectedly pregnant with the man in the cave’s child, causing her to flee to her childhood pen pal, a poet who shelters her while she decides what to do, as her body undergoes ever more intense transformations.

Much of the novel is hallucinatory and dreamlike, as the narrator slips in and out of various drug-induced states, leading to passages of intensely odd and startling beauty. It quickly becomes difficult for the narrator and the reader to distinguish between fantasy and reality – at one point she is convinced that she has killed someone whilst driving under the influence in her car, but is never able to find a trace of the person again, despite trying to track him down at the local hospitals and emergency rooms. The narrator lives in a twilight state in between guilt and freedom, enjoying the sheer edge of her new-found freedom whilst reflecting on her failed marriage and how she got here. The intensely personal nature of her uninhibited thoughts allow her to dissect her relationship with her ex-husband and her disappointments with the shape of her life so far with a disarming frankness.

Blood Red is a celebration of female autonomy from an unusual perspective. The narrator rushes headlong into both the actions and the consequences of her actions afforded to her by her new freedom from the restraints of married life. This extends to her exploration of her sexuality and to her experience of pregnancy, both of which she throws herself into with gusto. The narrator embraces the chaos, and if she’s not exactly in control of either her appetites or her body, she revels in the experience and the sheer joy of exerting her own agency. In this way, the novel is a powerful and uncompromising piece of feminist writing.

Ponce’s writing is extraordinary, and she can be wryly funny and emotionally devastating, frequently within the same sentence. Her writing moves from explicit descriptions of sex to abstracted sexual fantasies to sublimated embodied fears with dizzying aplomb, yet she is just as able to deliver shockingly personal confessionals that delve deep into her characters’ troubled psyches. Translator Sarah Booker deserves mention here as well, she does an incredible job of capturing the fire and intensity of Ponce’s writing and keeping the whole thing surprisingly easy to follow and understand.

Blood Red is a powerful and confrontational read, one that is unafraid to challenge its reader in its pursuit of its author’s unique vision. I can only hope that we will see more of Ponce’s writing translated into English, as her discomforting and vivid vision is one very much worth exploring.

Blood Red is available now on the Dead Ink Website